Commencement Speech: May 27, 1979

Listen to the full speech, by clicking the triangle: or read the transcript below.

I was told that my speech today should be a mixture of sentiment and humor, and that I should make people feel good. I sense behind that advice a fear that I will mar this ceremony with stridency and divisiveness. Why might I create bitterness? Because I lost my college. I am a former Kirkland student receiving a degree from Hamilton. Like some other women students at Hamilton I am not entirely happy with Kirkland’s fate, and not entirely convinced that the merger has gone through smoothly as many insist it has. Most of all, I’m afraid that within a few years, even without malevolence, Hamilton will manage to wipe out all traces of Kirkland.

For those of you who don’t know, Kirkland was the school across the street in which all the women in the class were originally enrolled, and which has since folded and been absorbed by Hamilton in a move loosely and inaccurately called a merger. What we lost in losing Kirkland was an alternative, and in that alone, we lost much. Each of us as individuals can seek out his or her own alternate routes to learning, but it is a rare opportunity to be backed up by an institution in that search. Our class was lucky enough to enjoy that opportunity for 3 years.

At Kirkland, there was the sense that students were trusted. Whether manifested in the first-name basis which is between most students and faculty, or in policies, such as independent study programs, which depended on a student’s self-motivation, there was evidence that the administration assumed that students were grown-ups. The fact that one could design her own major indicated that the school had a respect for the student’s individuality. The use of evaluations as opposed to grades also contributed to the student’s sense of her own uniqueness, and was based on the belief that students were interested in learning for its own sake, not for the sake of getting on the Dean’s List. Evaluations also encouraged students to compete with themselves rather than with others. In many ways Kirkland’s policies testified to the administration and faculty’s confidence in students. Kirkland had her problems, but one of her fine points was the dignity which she assigned to students.

In conversations about this speech, various people have urged me not to be divisive. That exhortation for unity, at any cost, has become some kind of watchword for the post-merger era. Unity, peace, congeniality have all become ultimate goals. They may be worthy goals, but they may also be attained at exorbitant cost, in which case we should examine our values.

Is unity possible, or even desirable, in an academic community? After all, what’s so wrong with division? Why are we so afraid of it? Certainly we cannot expect people to agree with each other, can we expect them to sacrifice convictions only for the sake of harmony? Unity is important, but it should not be the final criterion, especially in an educational institution. Supposedly education is all about learning and discovering. How can we learn and discover without challenging, questioning and criticizing? When we ask for unity, at any cost, we come dangerously close to imperialism. What ends up happening is that the minority is required to agree with the majority’s decisions, regardless of how firmly the minority believes in its own judgments. When one party says to another “Please don’t be divisive.”, it can mean, “Your opinion doesn’t count; mine does.” Rebelliousness for its own sake is destructive and we cannot encourage people to be demagogues. But we don’t have to fear dissent. If you can’t make waves in the academy, where can you make them?

Is unity possible, or even desirable, in an academic community? After all, what’s so wrong with division? Why are we so afraid of it? Certainly we cannot expect people to agree with each other, can we expect them to sacrifice convictions only for the sake of harmony? Unity is important, but it should not be the final criterion, especially in an educational institution. Supposedly education is all about learning and discovering. How can we learn and discover without challenging, questioning and criticizing? When we ask for unity, at any cost, we come dangerously close to imperialism. What ends up happening is that the minority is required to agree with the majority’s decisions, regardless of how firmly the minority believes in its own judgments. When one party says to another “Please don’t be divisive.”, it can mean, “Your opinion doesn’t count; mine does.” Rebelliousness for its own sake is destructive and we cannot encourage people to be demagogues. But we don’t have to fear dissent. If you can’t make waves in the academy, where can you make them?

Don’t we expect a certain amount of division in a place where opinions are being asserted? If my graduation speech turns out to be divisive, it’s not that I’ve created division among you. The fact is that I am speaking to a divided audience. To think that a speaker could take any position without disagreeing with a part of the audience is naïve at best. Sure, everyone wants to get along, and peace and harmony are noble goals, but what is the quality of the peace if there are people keeping their challenges and criticisms to themselves? Is it harmony when one person is free to state his or her opinion and a companion, for the sake of unity, is urged to nod in agreement whether or not, in fact, he or she does agree? That seems like a cheap peace to me.

People can have different views and still cooperate. I think that’s the ideal educational setting – where peace is highly valued, but not the point of requiring us to sacrifice truth.

One thing that strikes me as sad about our country is that, in an effort to be an American, many of us have lost our individual heritages. We have hidden, to the point of losing, our cultural differences. The great melting pot has indeed melted French, African, German, Latin American, Chinese, etc. into a bunch of Americans whose cultural heritage may only be represented by MacDonald’s golden arches.

In the same way, Hamilton’s quest for unity may lead only to attaining homogeneity, and in the loss of our differences, we’ll lose our individuality – eventually we’ll lose ourselves.

You can come to work out and even cherish differences. When I first came here, I hated the modern architecture at Kirkland and was much more drawn to the older buildings at Hamilton. During the last four years I have come to appreciate the new structures across the street, while maintaining my fondness for Carnegie and the chapel. We can see the value in different kinds of architecture: why can’t we likewise see the value in different kinds of attitudes and ideas? Just as the modern Burke Library has been integrated into the Stryker campus, why can’t different educational approaches be accepted within Hamilton’s structure?

The school could capitalize on what former Kirkland students and faculty have to offer, and could start making distinctions based on what’s good and bad, rather than on what’s “Kirkland” and what’s “Hamilton”. The Kirkland-Hamilton battle is history now. It’s time to judge ideas for what they are, not as party platforms for either faction. The acceptance or rejection of any proposal – whether it affects academic or social life – should depend on the intrinsic value of such a proposal, not on whether it reminds us of Hamilton or Kirkland. For example, if it is a good idea to have faculty residents live in dorms, then let us adopt the idea because it is a good one, not because it smacks of one college or the other. No academic policy should be judged as if it were a symbol for an institution.

The school could capitalize on what former Kirkland students and faculty have to offer, and could start making distinctions based on what’s good and bad, rather than on what’s “Kirkland” and what’s “Hamilton”. The Kirkland-Hamilton battle is history now. It’s time to judge ideas for what they are, not as party platforms for either faction. The acceptance or rejection of any proposal – whether it affects academic or social life – should depend on the intrinsic value of such a proposal, not on whether it reminds us of Hamilton or Kirkland. For example, if it is a good idea to have faculty residents live in dorms, then let us adopt the idea because it is a good one, not because it smacks of one college or the other. No academic policy should be judged as if it were a symbol for an institution.

************************************************************

The Kirkland class of ’79 has gotten the education of a lifetime. We have lived through the folding of our college. How many times does one live through a transformation like that? – the shift from one era to another? We’re a remnant of the old Kirkland cloth. At times we’ve clashed badly with Hamilton’s colors. At other times we’ve matched well. And whether we deny it or not, we are woven into the new Hamilton fabric. We are children of two eras – or perhaps children of neither era.

Both Kirkland and Hamilton have left their mark on this graduating class. I hope that will be the case for every graduating class which follows.

A house divided cannot stand. Hamilton will find its unity somehow. It can achieve unity either by waiting for three years to pass and more or less expunging the memory of Kirkland, or it can make a genuine and creative effort to preserve the best of both colleges. If Hamilton doesn’t choose soon to hold onto Kirkland’s gifts, we will surely lose them.

The most intelligent way to deal with division is not to ignore it nor to foster it, but to confront it and work out whatever problem it creates. That final stage, after differences have been recognized and dealt with, is real unity, real peace.

by Jan Sidebotham, ’79

Writing the Speech: The First Post-Merger Graduation

In the spring of 1978, I was in Paris for my junior year abroad. From a distance, the proposed merger on the Hill that I’d heard about didn’t hold a lot of significance.

The significance struck me once I was back on campus. I saw it in the faces and postures of my Kirkland professors. It was a done deal by then, and I felt a kind of institutional devaluing of all things Kirkland, including those of us who had enrolled there in 1975 and 1976.

But it was the mood of my professors that affected me most. These were people – Carol Rupprecht, Sybille Colby (who got out of there before I even got back from Europe), David Miller, Steve Lipmann, Nancy Rabinowitz, and my beloved advisor, George Bahlke – for whom I had deep respect and affection. How could these intellectual giants have been rendered powerless and voiceless?

I’m a Leo – someone who loves the spotlight, so it was no great valor that motivated me to “try out” for the opportunity to deliver the speech at the first co-ed Hamilton graduation. I wish I could say that I was the valedictorian, but I was simply the beneficiary of some kind of vote in my favor. A number of students gathered to go before a committee made up of teachers and students, seven in all. Richard Lee and I were elected to speak.

Getting the job was the smallest of hurdles. Soon after I was chosen, a Hamilton speech professor summoned me to his office so he could “help” me with the speech. I didn’t know him, and I didn’t completely trust Hamilton professors whom I didn’t know. (Whether accurate or not, a prevailing feeling among Kirkland students was that Hamilton professors counted us as unworthy to be Hamilton students.) The professor was condescending, and I was inarticulate. I remember him asking me if I had read Thales and then scoffing when I said I hadn’t. By the end of my session with him, I felt bullied and demoralized. I didn’t cry in front of him, but I cried afterwards. I went to my friend Mindy Wagner, and I think she suggested I go talk to the Rabinowitzes.

In their kitchen, Peter said to me, “Well, don’t talk to him anymore.” “Can I do that?” I asked. It felt so chicken-shitty and cowardly to avoid him. Peter said something like – if someone violates you, you don’t have to give him your valuable time or courtesy. His message was “Stay away from the guy. He’s bad for you, and you don’t owe him or anyone an explanation.”

It was advice that was important for the moment, but it was a turning point in my thinking. Courage or integrity didn’t always mean that you did the thing that was hard, unselfish, or painful. I didn’t have to face this guy again just to prove to myself or him that I was . . . brave.

So I didn’t make another appointment with him. I didn’t return his calls. My neighbors in Root answered my phone and said I wasn’t available. Finally, I got a note in my campus mailbox from a different Hamilton speech professor. It was very gracious, conceding that not everyone is always a good match and perhaps I would be willing to work with him, instead. So I agreed to rehearse my speech with him – in the chapel, with Peter Rabinowitz in attendance. The professor-by-proxy was satisfied, if not ecstatic, about my performance, and I was approved as a speaker for the graduation ceremony.

During that week between being chosen to speak and the commencement, President Martin Caravano’s assistant approached me and asked me not to be “divisive.” I’ll always remember that she pronounced it di VIZ ive, not di VICE ive (and I ended up pronouncing the word that way in my speech and always regretted it — it was phony coming from me.)

Others also expressed concern that I not wreck the ceremony with some kind of angry, anti-Hamilton speech. One so-called friend reported that a senior girl had said, “Oh, I hope she [me] doesn’t whine!” Yet many people were supportive. Carol Rupprecht said something like, “When Angela Davis was being harassed by the FBI, she said something like, ‘I’m just this little woman. What’s everyone so afraid of?’ You’re this nice, little WASPy girl, Jan. What’s everyone so afraid of?”

As much as I wanted to make it an anti-Hamilton speech, I am a people pleaser, and I didn’t want to make people angry. I needed a purpose, and I decided that I wanted to write the speech for the Kirkland professors – something that would honor them.

I made the speech. I haven’t read it in a while. I’m sure it was self-righteous. I have a little more compassion now for college presidents, CEOs, politicians, school heads, bishops – people who make important decisions. Rarely is it clear who the good guy is and who the bad guy is, and I’ve come to distrust any side that’s represented by vicious rhetoric.

It was a big moment for me, and for my mom who sat through the entire seven minutes of the speech – behind the Carovanos – worried that somebody was going to stand up and yell (at me), “Sit down and shut up!” No one did.

After all, who wants to mess with a Kirkland woman?

By Jan Sidebotham, K’79

Check back soon for the text of Jan’s 1979 speech.

Graduation, Kirkland Style

Caps and gowns. Pomp and Circumstance. Commencement speeches. What comes to mind when you think about your college graduation?

Caps and gowns. Pomp and Circumstance. Commencement speeches. What comes to mind when you think about your college graduation?

Of course, Kirkland seniors had a graduation ceremony. But it wasn’t quite typical. It was more of a maypole dance, birthday party, poetry slam, and traveling circus all rolled into one. It was so different, in fact, that LIFE Magazine covered it in its June 9, 1972 issue.

Like the college herself, Kirkland’s commencement was a mixture of traditional and unconventional, formal and informal. All in all, it was a joyful celebration enjoyed by the administration, faculty, and students and their families.

Carrying fresh bunches of daisies, graduating seniors marched behind our student flag bearers and a student bagpiper. We students wore our own colorful clothes—everything from jeans or shorts to flowery spring dresses.

Cheered on by other students, friends, and family, an informal procession of graduates wound around Kirkland’s campus to a large white tent pitched in the field beyond the dorms.

Our faculty and administration, decked out in their academic regalia, led the way. The ceremony itself took place inside the tent, which was filled with green and white balloons, streamers, students, and well-wishers. (In my case, my parents, sister, wire-haired terrier Scuffles, Florida grandparents, and Virginia aunt and cousin attended.)

Yes, we did have commencement speakers like other colleges do—but we also had an open mike. If a graduate chose to, she could speak to the assembled friends, faculty, and family.

President Sam Babbitt handed each of us our unique and priceless diplomas. And that was it!

At the college’s very last graduation, Sam said:

Yet what is good about Kirkland, what is lasting, is quite a separate thing from these buildings in which they have had their start, and it has a life quite independent of this place, beautiful as the place has been in which to nourish us. I want to talk about that, because it is those intangibles which all of us will take from Kirkland as we leave, and as we go, there, finally, will “Kirkland” also go . . . .

Kirkland has been a fine cause. And my message to you all—those who graduate today, and those who have been a part of it in any way—is that those things for which it has stood will continue to be a fine cause in which all of us may continue to serve.

Bagpipers and balloons.

What do you recall about your graduation?

How did you feel?

What did you say at open mike?

Click on this link for more graduation photos:

http://kirklandalums.org/graduations-gallery/

|

Did You Know? At the first post-merger graduation in 1979, displaced Kirkland (now deemed Hamilton) graduates conducted a silent protest. Many women placed a green Granny Smith apple beside the speaker’s podium. This powerful gesture has been carried on ever since. To keep the memory of Kirkland alive, Hamilton’s president is given a green apple from each graduate during commencement. Thirty years after the initial protest, Hamilton’s President Joan Hinde Stewart received 492 apples at graduation in May 2009. |

by Jo Pitkin K’78

Photos supplied by Katherine Collett, Hamilton College Archivist

Whew! Senior Projects

After my arrival at Kirkland, I heard the dreaded words senior project over and over from graduating seniors. In my sophomore year, I started worrying about mine. Every senior had to plan and execute this challenging task, with the help of her faculty advisor, in order to graduate.

At the end of our junior year, we submitted formal proposals for approval. As our projects began to take shape, we checked in with our advisors periodically, working in stages over the course of senior year. Like a doctoral candidate, each senior had a committee of professors who reviewed the completed project. Indeed, the projects themselves were worthy of many a graduate program.

In the 1970s, a few colleges—including Kirkland—required Senior Projects. By 2009, 64% of college students reported doing such a project (National Survey of Student Engagement). As of 2011, colleges that require them include Pomona, Reed, Hampshire, Carleton, and Occidental.

According to Kirkland’s 1976-77 Particulars:

The senior project, a one- or two-semester project in your field of concentration, is the culmination of your academic program at Kirkland. It demonstrates your competence in one or more disciplines, as well as your ability to work independently and to communicate clearly and effectively. Your senior project may take the form of a research paper, an exhibition, a presentation, or almost anything you and your adviser decide would be an appropriate conclusion of your academic program. The senior project is usually completed by May 1 of your final year.

How would I, with a dual concentration in creative writing and literature, show what I had learned in four years at Kirkland? I’m sure every Kirkland senior had the same jitters that I had. I’m also sure that we all shared a common feeling of immense satisfaction when our projects were concluded. Nothing I did in my undergraduate years was as enjoyable or as demanding. Here’s how mine turned out:

• I developed a reading list of Russian poetry, short stories, and novels in translation, including Kotik Lataev by Bely, Crime and Punishment by Dostoevsky, Mirgorod, or Four Tales by Gogol, Invitation to a Beheading by Nabokov, and Fathers and Sons by Turgenev.

• I wrote a sequence of poems based on the literature I read.

• I created and printed a broadside, Familiar Territory, of some poems from the sequence.

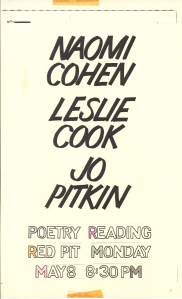

• I gave a poetry reading in the Red Pit with two fellow seniors who had also concentrated in creative writing, Naomi Cohen and the late Leslie Cook.

Every spring the campus bloomed with exhibits, performances, recitals, concerts, and readings by graduating seniors. It was impossible to take it all in. But the support and interest from other students was amazing. It was just the affirmation that a young scholar, writer, performer, or artist needed.

Here are some other examples of ‘75-76 Senior Projects listed in Particulars:

| A Photographic Portrayal of Women International Banking

Microscopic Study of the Submaxillary Gland of the Mouse A Study of Ambrose Bierce The Psychological, Social, and Cultural Effects of Rape An Examination of Criminal Law in China A Study of Welsh Nationalism Creating the Appearance of Movement in Clay Forms Implementation of a STRIDE Program in a Utica Day-Care Center Portraits and Self-Portrait: Writing a Collection of Five Short Stories An Analysis of French Stained Glass Windows in the Gothic Period Nineteenth-Century English Seduction Poetry An Ethno-Historical Perspective on Prehistoric Maya Settlement Patterns

|

Did You Know? Today, Hamilton College has a Senior Program. According to its web site, “Each department and program has designed a senior program to serve as an integrating and culminating experience for the major by requiring students to use the methodology and knowledge gained in their first three years of study. For many students, the Senior Program takes the form of a graduate-level honors thesis.” For example, Eva Hunt ’11 (Sociology/Studio Art) examined how developments in science and technology have impacted females’ attitudes about their bodies and their decisions about contraception. For her thesis Perceptions of Control: A Cross-Generational Study of Female Attitudes About Birth Control, she interviewed 11 current Hamilton female students and 6 Kirkland alumnae to determine if, how, and why attitudes and practices involving contraception differ between the two generations of women. |

Click this link to view more titles in the Kirkland College Archives at Burke Library.

My senior year was clouded by the fact that Kirkland would close forever after spring semester. An epic but ultimately fruitless struggle was waged in 1977 and 1978 to save our school. Students passed out petitions, wrote letters to trustees, staged protests, wore green arm bands. I don’t know how I had the discipline and concentration to finish my Senior Project. Somehow, under these stressful conditions, I managed to finish all my academic obligations.

By May, I was exhausted. I had covered all the bases. I read, I wrote, I published, I performed. The last hurdle was to have my Senior Project committee—Michael Burkard, Bill Rosenfeld, and Peter Rabinowitz—review my project. We met one afternoon at Michael’s apartment in downtown Clinton. After receiving mostly glowingly positive comments, Michael asked me, “So, what’s next?”

This is the way it was for many Kirkland students. We were encouraged and challenged. We were pushed academically, creatively, and intellectually. However, we did not view our accomplishments as a stopping point. With the Senior Project behind us, we asked ourselves, “What’s next?”

by Jo Pitkin K’78, with Jennie Morris K’72 and Eva Hunt ’11

What was your Senior Project?

What thoughts or feelings do you have about the experience today?

What were the challenges? the rewards?